Well, the countdown has begun in earnest now, to the publication of my third sea-change mystery and twelfth novel, Gerard Hardy’s Misfortune.

A few days ago, I was asked what clan tartan the cover designer, John Cozzi, had used.

It’s a hybrid, based on the Johnston, my family’s tartan on my father’s side, but with brown lines added. Those lines, and the pale green ones as well, suggest bars on a cell to me, and will perhaps to others too, when they read the story. My murder victim, Gerard Hardy, is found in a cell-like room at the end of a basement corridor, underneath Queenscliff’s historic Royal hotel.

The title is a play on The Fortunes of Richard Mahony and Hardy is a Henry Handel Richardson scholar, in Queenscliff to conduct some unorthodox research.

As I’ve said in previous posts, I find Richardson’s a compelling presence still, just up the hill from the Royal, at 26 Mercer Street, where she lived as a small girl with her mother and father and her sister, Lil.

Gerard Hardy’s Misfortune isn’t an historical novel, but the history of the Richardson family does play an important part.

And the glue that holds the whole thing together is provided by the main characters in my first two sea-change mysteries, Chris Blackie and Anthea Merritt.

Some time back I wrote a post on ghosts at the Royal Hotel in Queenscliff.

At last the long process of writing and editing my novel about a murder in the basement of the Royal is coming to an end. I’m involved in discussions about the cover, which will be designed by the incomparable John Cozzi, who created the cover for the second book in my sea-change mystery series, The Swan Island Connection. I’ve just sent John some photos of the haunted old hotel.

Reading through my manuscript for the last time, I was surprised by the importance of ghosts. That sometimes happens to a fiction writer; she’s busy focussing on one theme or another, then goes back to the story and finds that something else has been important all along.

Brigid Magner is a literary scholar and lecturer at RMIT. Speaking about her research on literary tourism, Brigid makes the point that houses where famous writers have lived are often felt to be haunted.

“But the term ‘haunted’ does not always refer to ghosts as such. It can also refer to a ‘haunted’ state which can either be a pleasant communion with a bygone spirit, or it might entail distress and anxiety. It can also refer to the old ‘haunts’ of notable individuals.”

In my story, the young man killed in the Royal’s basement was a Henry Handel Richardson scholar, visiting Queenscliff for a tarot reading which he hoped would connect him to the spirit of his heroine.

In the 1870s, the child who was to become Henry Handel Richardson lived with her family at 26 Mercer Street, just a hop, step and jump from the Royal. No one has seen or heard or felt a ghost at 26 Mercer Street so far as I’m aware, but the Royal is reputed to be haunted from its basement to the top of its tower. Built in the 1850s, it was Queenscliff’s first morgue.

Ethel Richardson – or Ettie as she was known when she was a small girl – believed the spirits of the dead could communicate with living human beings, as did her father, Walter and her sister Lil. Ethel maintained this belief to the end of her life, though she was secretive about it.

I thought of all of this as background to a murder mystery, but then somehow it became more than background. Not that my main characters believe in ghosts or spirits; they don’t. But they are influenced by them nonetheless.

One suspect sees visions and has done since her childhood. Chris, my police constable, is sympathetic, but wary at the same time. Then one night he ‘sees’ Mary Richardson, Ethel’s mother, hurrying home from the fort where she has been struggling to learn book-keeping and Morse code so she can support her daughters.

Chris, who has always admired Mary, is moved and shocked.

I guess is that, looking back at the novel now that it is finished, I realise there’s a thin membrane, a kind of gauzy veil, separating my policeman and woman from the characters they are investigating. There aren’t two sides of the fence; there’s no black and white. This blurring of boundaries interests me. I hope it will interest readers too.

Towards the end of As The Lonely Fly, a mother writes to her daughter about a woman who has been a strong influence on both their lives, and from whom they have not heard for eight years. This woman is the mother’s sister and daughter’s aunt Clara, who changed her name to Chava when she emigrated to Palestine in 1922.

‘My sister was an idealist, and it is possible that in spite of all that has happened she remains one to this day. We are all idealists, why else would we be here, but she was more so. There wasn’t a practical bone in her body. She didn’t know people.’

As The Lonely Fly is an epic work of fiction, with a huge cast of characters, moving from Palestine under the British Mandate, to Russia, to the United States and back to Palestine. But Chava remained for me a focal point throughout. I did not find her impractical, or ignorant of people; quite the opposite in fact. So how is it that Chava’s sister Frieda, who follows her to Palestine and who, with her husband, builds and runs a successful noodle factory, could be wrong? Or am I wrong? What are readers meant to think?

Chava joins the Labour Battalion, draining a swamp, then building roads and planting trees. The battalion attempts to create good relationships with its Arab neighbours. Chava’s beliefs are put to practical tests, which are brilliantly evoked, and for a while it seems as though the group might have some chance of lasting success.

‘It took them a day to dig out the holes and insert the trees, and the next day there were more. They planted them along the shy river. When the sun slipped towards the sea they lit another fire. Stunned by fatigue, Chava stared mutely at the heat shimmering above the flames, everything at the fire’s periphery seeming to lose anchorage and shape.’

Chava helps Zipporah, the niece to whom the letter is addressed, emigrate to Palestine, and helps her find work as a housekeeper, though she longs to be ‘out in the open, building a city, building roads’. But jobs are scarce. Dowse’s descriptions of daily life give her characters and their idealism a very practical core.

When Zipporah is taken to a plantation at Petah Tivkah she’s thrilled.

‘For Zipporah it was all a wonder. Row upon row of citrus trees stretched out, all a neat size, their leaves the same dark ceramic green. The air smelled sweet though the blossoms had gone and the fruit was still ripening; she imagined the sweetness came from the sap itself. The hills were studded with grape-heavy vines, the soil was drained a rich chocolate brown, watered with channels from the river and underground springs. How often had she heard this had once been a swamp? It was another thing to see.’

During the day they work; at night they dance and sing and argue about politics. As time passes, Chava’s group, wanting Jews and Arabs to unite in an international workers’ movement, though divided amongst themselves as to how to achieve this, becomes isolated, as the tension, then violence between Jewish settlers and Arabs increases.

While all this is happening, Chava’s younger sister, Marion, (the anglicised form of her name), and her parents are trying to make a different kind of new life for themselves in the United States. Marion’s story is told in counterpoint to Chava’s and Zipporah’s, often through letters, though Marion does visit Israel at the end of the book.

The dreams of the immigrant are a constantly recurring theme in As The Lonely Fly, expressed in songs, in conversation and argument, in the hope of safety and freedom from persecution, in images of physical toil that mean something because they are contributing to building a home. Always there is the search, through Dowse’s questioning and restless prose, to embed these dreams in daily life, to make daily life in the ‘new’ country a sufficient answer. But in Palestine in the 1920s and 30s, daily life can never be separated from its political context – the machinations of the British, the rise of Hitler and Stalin.

Dowse relates the collapse of Chava’s dream with great poignancy and delicacy, following her deportation to the Soviet Union after she is jailed for supporting Arab riots; while in Palestine, after the 2nd World War, the state of Israel is being forged.

As the title suggests, As The Lonely Fly is quintessentially a story of exile and migration; and for humans, if not for birds, this is a lonely business. Each of the three women the novel centres on must make her own decisions and adjustments, and, perhaps inevitably, end up being misunderstood by other members of the family. Sometimes decisions are taken out of a character’s hands, as with Chava’s deportation, but even without that stark example, an individual’s dreams and hopes for justice, her longing to make a contribution, are bound to be compromised. As The Lonely Fly tells an important, timely story, through its rich variety of characters and beautiful prose.

As The Lonely Fly can be pre-ordered from For Pity Sake Publishing here.

My double review of the bird man’s wife by Melissa Ashley and The Atomic Weight of Love by Elizabeth J. Church was published in the Fairfax newspapers last weekend.

Seeing the covers together like this, it’s clear that both novels are about birds. the bird man’s wife tells the story of Elizabeth Gould, wife of John Gould, the famous ornithologist. It was in fact Elizabeth, not John, who drew and painted most of the illustrations in The Birds of Australia, and author Melissa Ashley has righted a historical wrong in bringing Elizabeth’s name, and life, out of obscurity.

As well as performing this worthwhile task, Ashley has written a fascinating and absorbing novel. Please follow the link above to read my review in its entirety.

Readers first meet Elizabeth in 1828, as a young woman in London, where she first meets her future husband, and follow her to her death, of puerperal fever, after the birth of her eighth child, aged just thirty-seven.

Elizabeth’s life-long curiosity about the natural world links her, across more than a century, to Meridian Wallace, the main female character in The Atomic Weight of Love, who goes bird-watching on her own and is not the slightest bit interested in playing with dolls. Meridian is a brilliant student who falls in love with a physics lecturer twenty years her senior, marries and then follows him to Los Alamos, postponing, then finally abandoning her graduate studies in ornithology. In the middle decades of the twentieth century, Meridian is not forced to endure successive pregnancies – she never has children of her own – but she submits to the husband with whose intellect she first fell in love.

Both books are beautifully produced, the birdman’s wife in particular; it’s a hardback, the end papers including some of Elizabeth Gould’s finest illustrations.

On October 7, eight female crime and mystery writers will converge on Cobargo, just inland from Bermagui on the NSW coast, to take part in their inaugural crime convention.

http://fourwinds.com.au/whats-on/sisters-in-crime/

The writers are an eclectic mix, from a gynaecologist living in far north Queensland, Caroline de Costa, to a former member of the RAAF, who also has a BA in medieval history, Ilsa Evans, to a writer of historical crime (Sydney/1930s), Sulari Gentill, to yours truly, author of a Canberra-based quartet, now embarked on a sea-change mystery series.

One of the festival organisers, in a welcoming email, said that they were washing the streets of Cobargo in honour of our arrival. Thank you, Louise!

While this is an attractive idea, I wonder if it really fits a collection of crime writers, who might be more comfortable with dirty streets, even blood-stained ones?

Jennifer Rowe once referred to crime writers as ‘good housekeepers’, by which she meant that we like to tidy things up, which has an element of truth in it, at least for some exponents of the genre. But even PD James said that order is never really re-established at the end of her novels.

My approach to clean streets is that I like to dig beneath them – hardly surprising since I lived in Canberra for 30 years and turned to mysteries as a way of writing about that city.

Now what exercises my imagination is what might lie beneath the surface of an idyllic coastal town….

Authors sometimes grumble about their editors, and the question I’ve chosen as a title for this post is one I’ve often heard authors repeat.

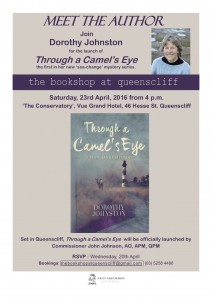

But I’m pleased to say that I have a wonderful editor for my new novel, titled The Swan Island Connection. This novel is a sequel to the first of my sea-change mysteries, Through a Camel’s Eye, which was published in April by For Pity Sake Publishing.

The editor’s name is David Burton. David, an editor with For Pity Sake, is also an award-winning playwright and theatre director, whose plays include April’s Fool, Orbit and The Landmine Is Me. He has written a memoir titled How to be Happy. As an editor, Dave possesses that rare quality, (rare in my experience), in that he takes the trouble to see into an author’s mind, think about where he or she is trying to get to, and how he might help them to arrive.

Dave read what I am now calling the Dog’s Breakfast Draft (DBD) of The Swan Island Connection and wrote a nineteen page report. When I first saw the report, I felt daunted. There must be an awful lot wrong with the manuscript, I thought, to require this many pages. But the report, while critical, is constructively so, and that makes all the difference. In tone it is far from negative, and is full of helpful ideas and suggestions. And the very fact that someone who know what he’s talking about has paid such close attention to my DBD has given it, and me, a whole new lease of life. Thank you, Dave!

The Swan Island Connection will be my eleventh novel to be published. The first was in 1984, and since then I’ve run the gamut from good editors to woeful. Amongst the good I number Jenny Lee and Lois Murphy, and amongst the woeful, who shall be nameless, the lesbian separatist who read my book about the British atomic bomb tests at Maralinga. This was not, on the face of it her subject, and she made no effort to meet me half, or even a quarter of the way. Another was the editor who used to ring me at 6 PM, just before she left the office, to discuss editorial points that required thought and concentration. At the time this editor was assigned to me, I had a four-year-old and a baby who wouldn’t sleep, plus a deadline for the manuscript. One horrible evening I shouted at her down the phone, ‘Don’t you realise it’s jungle hour!’ I’ve felt ashamed of that outburst ever since.

Then there was my New York editor whose publishing company had bought the first two of my Sandra Mahoney Quartet (mystery novels set in Canberra, where I lived for thirty years). This editor, though I respected him, and of course felt grateful that my books were going to be published in the United States, insisted that I change all my galahs to parrots, all my jumpers to sweaters, and that I massage the text in various other unsavoury ways in order to make it more attractive to an American readership.

Recalling all that, I’ll say again – thank you, Dave!

And thanks to Bill Whitehead the cartoonist for reminding me how much I like Dickens.

My reviews of Georgia Blain’s Between a Wolf and a Dog, and her young adult novel, Special, were published in the Fairfax newspapers this weekend. (In Australia, it’s a long weekend for Anzac Day.)

Readers of this blog will know that I don’t copy my reviews into my posts. You can read the reviews of Blain’s two books here.

Instead, I add a few thoughts that I didn’t have the space for, or go off on a small tangent of my own.

While Georgia Blain was writing Between a Wolf and a Dog, in which one of the main characters, a woman in her seventies, has brain cancer, she discovered that she herself had a malignant brain tumour. She was mowing the lawn one day when she collapsed and was taken to hospital.

There’s a very good interview with Charlotte Woods in the Fairfax papers, detailing what Blain went through, and she also wrote a series of articles about it in The Saturday Paper.

You can imagine what you’d feel like if that happened to you. You’d scarcely be able to believe that irony, or fate, could be so cruel.

Blain went back to editing the novel, which isn’t autobiographical, and produced a very fine piece of work indeed.

It’s a co-incidence that, the same weekend my reviews were published, I started reading the manuscript for The Dalai Lama in My Letterbox, sub-titled One woman’s Big Breast Adventure, by Jennifer McDonald. The books are very different – McDonald’s is based around the blog she started when she was first diagnosed with breast cancer. It’s warm and witty, at time very funny, intimate and courageous.

Blain’s is fiction, and there are other important characters besides the cancer sufferer. The two books have one thing in common, though; neither is the least bit sentimental.

Jennifer McDonald, I’m proud to say, is the Principal at ‘For Pity Sake’, publishers of my latest novel, Through a Camel’s Eye.

One last comment on Between a Wolf and a Dog. The title comes from a French expression: ‘l’heure entre chien et loup’. This means ‘the hour between a dog and a wolf’, and refers to dusk, or twilight, when an animal, possibly threatening, observed at a distance, is no longer a dog, but not yet a wolf. It’s that unsettling time which, in English, we sometimes call ‘the witching hour’. Blain has inverted the French saying to make it refer, not to dusk, but dawn, the time when the novel begins, with one of the characters who has passed a sleepless night.

My review of Olga Lorenzo’s The Light on the Water was published in the Fairfax newspapers this weekend. As usual, when posting about a newspaper review, I’m not going to repeat the points I make about the novel, but, this time, add some information about the author’s life.

Olga Lorenzo was born in Cuba a month after the revolution that brought Fidel Castro to power. Her family left Havana for Miami when she was not quite three years old on one of the ‘Freedom Flights’.

‘It was terrible,’ Lorenzo says. ‘There were no refugee programs in place in Miami. We moved to what was called Little Havana, and everyone was speaking Spanish around me, so it wasn’t a cultural transition. The shock was that I had no toys, we had no clothes, there was no food, we had no furniture.’

When she was 22, Lorenzo moved to Australia and finished her undergraduate degree at Melbourne University, where she later went on to do a Masters and a PhD in creative writing. She currently teaches creative writing and has also worked as a journalist and sub-editor for the Melbourne Age.

Her first novel, The Rooms in My Mother’s House, published in 1996, though clearly fiction, draws largely on her family’s experiences. Twenty years on, The Light on the Water tackles very different subject matter, but with Lorenzo’s hallmark compassion and skill.

Thanks to Sydney Morning Herald literary editor, Susan Wyndham, for mentioning my forthcoming novel, Through a Camel’s Eye, at the end of my review.

‘Dorothy Johnston’s novel Through a Camel’s Eye will be published in April by For Pity Sake.’

Through a Camel’s Eye will be launched on April 23rd at the Vue Grand Hotel in Queensciff. Hope to see you there!

When I read a description of The Three Princes of Serendip on Gert Loveday’s blog, I immediately felt anxious. Here was an ancient story that began with a missing camel. My new novel, Through a Camel’s Eye, due for release next year by Sydney-based publisher For Pity Sake, and up to the proof-reading stage, begins in exactly the same way. What if I had somehow, without remembering or realizing, absorbed the whole plot and transferred it to modern times, to the small town of Queenscliff close to where I live?

The camel in the old Persian tale is a native, as are the three young men who notice his tracks and cleverly deduce (in Sherlock Holmes fashion) all kinds of facts about him. My camel is an exotic and enchanting creature, at least he is to me. As I read on, I was relieved to find many other differences as well.

So I don’t have to face the ignominy of having pinched my plot. But the word ‘serendipity’, which Horace Walpole coined, using The Three Princes of Serendip as an example, is relevant to my story, and accurately conveys the way my protagonist goes about his detective work.

Chris Blackie, senior constable at the generally quiet Queenscliff police station, stumbles on an important clue while looking for camel tracks in the sandhills. His methods of deduction and inference, and those of his assistant, Anthea, fall well within the ‘serendip’ tradition. The clue discovered in the sandhills starts them off on the search for a missing woman.

‘..they were always making discoveries, by accidents and sagacity, of things which they were not in quest of..’ Walpole says, referring to the princes in a letter to Horace Mann.

Right!

I discovered that the Serendip (an old name for Sri Lanka) story is one of those that fairy-tale scholar Marina Warner describes as having ‘seven league boots’; that is, they can be found all over the world. In India, the tale involves an elephant, while in Palestine and Arabia it’s usually a camel that has disappeared. Walpole substitutes a mule, perhaps because mules were more familiar to him.

In cultures where tracking is not only an important, but an essential skill, it’s no surprise that such stories abound. I wish I could find an Aboriginal one to include here. Never mind, I’ll just keep looking and maybe…

My review of The Landing was published in the Fairfax newspapers this weekend. It’s Johnson’s eighth novel and a fine one.

As usual, I’m not going to repeat the points I make in my review here, on this blog, but add a bit of musing round the edges that I didn’t have space for in 700 words.

This time my musing is about catalogues and lists. Johnson has several of them, mainly of the beauties around the lake where her protagonist, Jonathan Lott, has his holiday house. I came across her first one with a sense of recognition.

Why do authors make lists? Obviously they do so for a variety of reasons, but one of the main ones, it seems to me, is that by adding up and counting you, the author that is, can put off getting to the end. Enumeration can delay having to face what happens when you run out of items.

This is most apparent when the author, or character through whom she or he is speaking, knows that fear, or worse, the terror of complete disintegration, hides beneath, or in the middle of, the list.

The critic Ivor Indyk put it this way – and I’m paraphrasing, I don’t recall his exact words – when it comes to lists, he said, the real question is knowing when to stop.

That’s one function of lists in literature, as I see them. Another is the more fundamental and primitive urge to name. You name the things around you, and go on naming them, in an act of bearing witness that you hope will carry meaning in addition to the name.

‘Glory be to God for dappled things,’ says Gerard Manley Hopkins in Pied Beauty, and then goes on to list them, with joy, wonder, and thanks-giving.

And then there’s Proust, the acme and pinnacle of list-makers, who does all of the above.