Last Friday, while walking 3 dogs, I tripped, fell heavily and broke my left wrist. Now I’m facing 6 weeks without being able to swim, drive or play the piano.

It’s amazing the number of dog-walking mishap/ falling down/ breaking limb/ stories I heard during my 24 hours in hospital.

One of my nurses broke her ankle after slipping on some perfectly ordinary leaves. My anaesthetist told me how he was riding his bike with his dog running obediently alongside when all of a sudden the dog dashed in front of him. He went straight over the handle-bars, but fortunately wasn’t hurt. The culprit? A pedestrian walking towards them carrying a packet of sausages. This story was made all the more vivid because the anaesthetist was sticking needles into me at the same time as he was telling it.

I’ve just tried playing a few bars of a favourite piece on the piano with my right hand only. I can see I’m going to have to do a lot of experimenting/improvising over the next few weeks.

Soon after I started blogging, I wrote a post about the importance of music to my father when he was suffering from Alzheimer’s disease, and about playing the piano at different writers’ residencies around the world.

Thinking about this, I was reminded of the poet Tomas Tranströmer and how he taught himself to play the piano left-handed after suffering a stroke.

‘Tranströmer began playing piano as a child and it became for him in his life a passion matched only by his career as a poet. Musical references and composers often appear in his poems. In 1990, he suffered a stroke that paralyzed the right side of his body and affected his speech.

This description, from the poet’s official website, and the photo of Tranströmer sitting at his piano, focused and dedicated, his right hand tucked up and his left hand making music, moved me very much. Music is as important to me as writing, and my inconvenience is nothing compared to what Tranströmer faced. Now, when I sit at the piano trying to pick out melodies with one hand, I’ll be thinking of him.

This poem is copied from Tranströmer’s official website. I don’t know if he wrote it before or after his stroke.

Allegro

After a black day, I play Haydn,

and feel a little warmth in my hands.

The keys are ready. Kind hammers fall.

The sound is spirited, green, and full of silence.

The sound says that freedom exists

and someone pays no tax to Caesar.

I shove my hands in my haydnpockets

and act like a man who is calm about it all.

I raise my haydnflag. The signal is:

“We do not surrender. But want peace.”

The music is a house of glass standing on a slope;

rocks are flying, rocks are rolling.

The rocks roll straight through the house

but every pane of glass is still whole.

This is the third in my series of posts about Australian poets. The first two are Suzanne Edgar and Joan Kerr.

Geoff Page is one of Australia’s best known and widely-published poets. He is based in Canberra and has published twenty-one collections of poetry as well as two novels and five verse novels, and has won many awards. Rather than include a lot of biographical information in this post, I suggest readers follow the link to Irma Gold’s excellent interview.

The Deputy

for J.F.

Driving daily into work,

he feels them equally as pressures,

atmospheric almost,

one more urgent than the other

but pressure all the same.

Both could justify a life,

one with what the young retain

and carry with them through the years,

the other more diffuse

and closer to the core,

resonances rising

from something deeper down,

more opaque than God perhaps,

rhythms, lines and images,

a gift that needs real readiness

before it can arrive.

Of course, one may excel at both.

No doubt a man may serve two masters.

Last year he taught them Doctor Faustus,

the senior class he still keeps on.

He thinks about the famous bargain,

the heavy freedoms of its power,

the good opinion held so widely,

the parent-teacher nights and, yes,

the jokes he makes at school assemblies

to show he’s serious.

At home though there’s a desk

With untouched paper and a screen,

an ideas file, a journal,

a mix of discipline and licence

to bring in pocket money only,

scuffling below the dole.

A friend of his has chosen this,

insecure and frugal

and prone to bitterness.

A third has signed a smaller deal,

holding off from higher slots

if ever they were offered.

Who is his Mephistopheles?

It’s not the principal.

He thinks perhaps they are collective,

these senior teachers who respect him,

who cannot let him go,

who see that he can make things happen

and keep a keel on course.

To them, this other life he has

is hardly more than self-indulgence,

a foible or some pleasant extra,

a flourish or addendum

to make a CV more compelling.

His watch says 8 am.

He turns into the car park now,

an hour before the world begins

its unforeseen complexities,

its smoke and mirrors of the human,

the needs that only he can meet.

The car is small and European,

very fast from nought to ninety.

He walks towards the building…

and sees, back home, that writing desk

patient in its shaft of light,

the blank page and a keyboard waiting,

the pressure of the poem.

‘The Deputy’ appeared in Meanjin 2, 2014. Thank you, Geoff, for allowing me to reproduce it here, and to Meanjin for publishing it.

I read the poem with an instant, deep feeling of recognition. In sixty-three lines, it says an enormous amount about the life of art, the choices and hard bargains, and the ways these are carried within a person life-long.

The voice is quietly authoritative, unsentimental, uncomplaining. The deputy headmaster, who is also an artist, must weigh up and doubt and compare, and go on doing so. This is his destiny. But it’s not an intellectual exercise – the pressures are heart-felt.

And the last line is superb, shining undimmed by the teacher’s daily, ‘other’ life, yet given meaning by it and by the poem as a whole.

I was reminded of the last stanza of Yeats’s ‘Meditations in Time of Civil War’, and ‘the half-read wisdom of daemonic images’ with which Yeats comforts himself, while understanding that Page’s poet/public man is a very different character.

A wonderful poem! I hope many readers get the chance to discover and enjoy it.

Last May, ABC radio national’s program, Poetica, focussed on the villanelle.

The villanelle is a very old poetic form, medieval in fact, but it has become popular with contemporary poets in Australia.

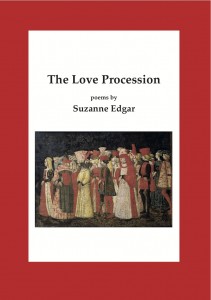

In this blog post – the first of several I plan to write about poetry, which I love reading, but don’t write myself – I am focussing on the Australian poet Suzanne Edgar, who has this to say about the villanelle.

“The villanelle is an old Italian lyric form that was originally sung; it needs a consistent metrical musicality. There are rules about its rhyme scheme, the refrain lines and their position in the poem. The refrain needs to be strong enough to carry the emotional load of its repetition. My villanelle ‘After Drought’ was written in a joyful mood, during a downpour of summer rain. It was included in Mike Ladd’s `Poetica’ program.”

AFTER DROUGHT

How sweet it is, the sound of falling rain

after years of unrelenting dry,

I thought I’d never hear the sound again.

The falling plays a favourite refrain

as soft as stroking, quiet as a sigh.

How sweet it is, the sound of falling rain

that soaks the bark and leaves a greenish stain

as if it had been coloured with a dye.

I thought I’d never hear the sound again.

Deep ruts are overflowing in our lane

and clouds are spreading froth across the sky.

How sweet it is, the sound of falling rain ‑

new droplets form on wall and window-pane

making shapes that glitter, blend and die.

I thought I’d never hear the sound again

of steady raindrops humming in my brain

their plaintive rhyme; for no one will deny

how sweet it is, the sound of falling rain.

I thought I’d never hear the sound again.

‘After Drought’ was first published in Quadrant (June 2008). It inspired a piece of textile art, exhibited by Lynne Taylor at Fairfield City Museum & Stein Gallery, N.S.W., in May 2009. Ian MacDougall composed music for it which he’s sung (with viola, violin and guitar backing) and recorded on a CD. This is in the School of Music library, A.N.U. The CD was played on `Macca All Over` (ABC RN) on 3 March 2013.

The more sombre `Resolution’, in Edgar’s collection The Love Procession (Ginninderra Press, 2012), involves a domestic argument that goes around and around in circles. “It should not be read as strictly autobiographical though,” says Edgar. “Matthew Arnold’s words are always on my mind: `The despotism of fact is unpalatable to the Irish.’ ”

RESOLUTION

We’d argued through a long and foolish fight.

Though there was nothing useful left to say

it simmered in the evening’s muted light.

He’s always bloody sure he must be right,

the sort of man who’s bound to get his way –

we’d argued through a long and foolish fight.

I shoved our tell-tale budget out of sight

to read again some later, peaceful, day.

It simmered in the evening’s muted light.

He swore he had suspected I was tight,

repeated it was high time I should pay.

We’d argued through a long and foolish fight.

I took the bills and set each one alight

till they, and I, became an ashy grey

that simmered in the evening’s muted light.

Because I couldn’t face a sleepless night

I sold some shares and paid up straightaway.

We’d argued through a long and foolish fight

that ended in the evening’s muted light.

Edgar comments that “Stephen Fry’s The Ode Less Travelled (Arrow Books 2007) provides witty advice about the villanelle as a vehicle for ‘rueful, ironic reiteration of pain or fatalism’. I recently finished the rather mournful ‘Lament’; it has the refrain,

‘Thinking, tonight, of all the books we’ve read,

I know we’ll miss ourselves when we are dead’.

Wendy Cope, however, has written some amusing examples, see ‘A Villanelle for Hugo Williams’, in her Family Values (Faber 2011). This poem displays the form’s rules in the guise of advice to another writer who’d got them wrong!

Other old French forms I’ve used are the rondel, ‘River and Rock’, and the triolet, ‘Malunggang’, both in The Love Procession. Once the formal pattern for such poems is in place I will overlay it with naturalistic or colloquial diction and tone, to avoid any effect of rigidity. This approach was also used in the petrarchan sonnet ‘Corteo d’amore’ which begins that book.

Poetry arises from watchfulness and alert waiting. There remains the exciting, rejuvenating work of refining. I would hate to be labelled a formalist, a modernist, or any other `ist’. It would be restrictive, whereas I feel free to write in any way I like. I agree with Camus: ‘Poetry that is clear has readers. Poetry that’s obscure has commentators’. I mistrust the current vogue, particularly among academics and their imitators, for writing poems in which meaning is cerebral, convoluted and difficult. They write only for the page, have turned poetry into words.”