My Big Breast Adventure is a path breaking book which crosses the boundaries between a factual account of one woman’s breast cancer treatment, a philosophical discussion about what it means to be sick – and what it means to be well – and a celebration of humour in the face of adversity.

‘..when one has just had a cancer diagnosis and is about to undergo major surgery, laughter is at a premium and does not come easily,’ Jennifer McDonald writes.

Yet an early chapter heading reads ‘Cut, Poison, Burn and Laugh’ and time and again I found myself laughing while reading My Big Breast Adventure, which is based on the author’s blog posts and includes comments by readers. When I stopped to think and wipe my eyes, I asked myself why I was laughing when the author was going through hell. Answer: I was laughing because she made me laugh. McDonald’s humour is the buffer between her threatened sanity and the daily, weekly, monthly rounds of tests and chemo, radiation, more tests and more chemo.

There are many examples I could choose: here is one about hair loss.

‘I cut all of mine off before starting treatment even though my carers told me the hair probably wouldn’t fall out until about week three. Why wait to be bald I say? No word (or movement thankfully) on the eyebrows and lashes as yet. As my sister reminded me though, we McDonald girls come from staunch Celtic, Methodist stock which means we have eyebrows like John Howard and leg hair like the family dog.’

McDonald’s humour is like a dance with a quick, flicking two-step at the end. It is insouciant, irreverent, compassionate and warm. As readers would expect, anger and sadness, nausea and crushing fatigue are part of the story. They are acknowledged and dealt with. Jokes don’t take the dark side away; they make it into something more.

‘..I believe there are much worse things than death – being kidnapped by Boko Haram, having your business put into general administration, sitting by the bedside of a dying loved one, or living in Tony Abbott’s (Australian Prime Minister at the time of writing) electorate. Hang on, I do live in his electorate –what the FEC?’

FEC is an acronym for an extra chemo cocktail which McDonald took for nine weeks after her twelve-week standard chemo program was finished. For Father Ted fans, it’s also an irresistible reminder of Mrs Doyle offering a cup of tea to Father Jack. McDonald of course makes the most of this connection.

When discussing the importance of active acceptance, the author refers to Eckhart Tolle’s The Power of Now, and on the next page quotes a poem by an ancient Sufi mystic. Quotations and references abound, but they never feel intrusive in the text, or stuck on for effect. They don’t detract from the central story; they enrich it.

McDonald makes the point that, while, she has striven for accuracy in describing her treatment and its effects, both physical and emotional, My Big Breast Adventure is not a therapy manual. Though she refers throughout to aspects of traditional and complementary medicine, she stresses that her approach is personal; she is not setting out to tell others what to do when they receive a cancer diagnosis, or where to look for help and guidance. Yet I’m sure her book will be a help and guide to many, not least because of her unfailing sense of humour.

- My Big Breast Adventure can be purchased for $24.99 paperback and $9.99 ebook from For Pity Sake Publishing.

My double review of the bird man’s wife by Melissa Ashley and The Atomic Weight of Love by Elizabeth J. Church was published in the Fairfax newspapers last weekend.

Seeing the covers together like this, it’s clear that both novels are about birds. the bird man’s wife tells the story of Elizabeth Gould, wife of John Gould, the famous ornithologist. It was in fact Elizabeth, not John, who drew and painted most of the illustrations in The Birds of Australia, and author Melissa Ashley has righted a historical wrong in bringing Elizabeth’s name, and life, out of obscurity.

As well as performing this worthwhile task, Ashley has written a fascinating and absorbing novel. Please follow the link above to read my review in its entirety.

Readers first meet Elizabeth in 1828, as a young woman in London, where she first meets her future husband, and follow her to her death, of puerperal fever, after the birth of her eighth child, aged just thirty-seven.

Elizabeth’s life-long curiosity about the natural world links her, across more than a century, to Meridian Wallace, the main female character in The Atomic Weight of Love, who goes bird-watching on her own and is not the slightest bit interested in playing with dolls. Meridian is a brilliant student who falls in love with a physics lecturer twenty years her senior, marries and then follows him to Los Alamos, postponing, then finally abandoning her graduate studies in ornithology. In the middle decades of the twentieth century, Meridian is not forced to endure successive pregnancies – she never has children of her own – but she submits to the husband with whose intellect she first fell in love.

Both books are beautifully produced, the birdman’s wife in particular; it’s a hardback, the end papers including some of Elizabeth Gould’s finest illustrations.

To celebrate Christina Stead week this year, Lisa Hill at ANZ Litlovers is hosting a selection of reviews and appreciations of Stead’s work. As my contribution, I’ve written an appreciation, rather than an objective review of For Love Alone.

For Love Alone meant a great deal to me when I first read the novel in the mid nineteen seventies, a time when I was teaching myself to write. It is among the top ten, if not top five novels from which I learnt the most. The mid nineteen seventies was also the time I met Christina Stead, while she was a writer-in-residence at Monash University. This post – which is really more of a personal testament than a critique of the novel – is not the place to describe our meeting. Suffice to say, Stead struck me as both gracious and formidable – gracious in that she had taken the time to read and think about a manuscript I’d sent her – formidable, as well as accurate, in her criticism of it.

While I learnt much from For Love Alone, I understood, young as I was, that it would be vain and foolish ever to imagine I could write like its author. But I identified with the struggle of Stead’s protagonist, Teresa Hawkins, to better herself through education, to scrimp and save in order to afford the fare to Europe. I also identified with the mistake she made in falling in love with the wrong man – not only a kind of generic ‘wrong man’ – but a man who was also her teacher.

And I fell in love with Stead’s prose, her language that is rich and deep, extraordinarily well orchestrated, heart-felt.

Jonathan Crow, the tutor who turns out to be nasty and self-serving, is the catalyst Teresa needs to get away from Australia, from Sydney. But what a Sydney Stead creates in the early parts of the book! I can never go to Watsons Bay without recalling her descriptions of the water and the summer heat, and Teresa and her sister Kitty, dressed in their best, heading off to their cousin’s wedding.

Stead’s London is the London of the 1930s, where Teresa finds work with the American radical, James Quick, a man who finally wins her affection and returns it. The title, For Love Alone, I have always read as ironic. It is not ‘for love alone’ that Teresa triumphs and learns to forge her own path; it is certainly not for romantic love, and she turns her back on the duties that might have kept her in Australia as a consequence of loving her immediate family.

During her lifetime, Stead was often maligned and misunderstood, the power of her prose sometimes frightening off readers and reviewers, not to mention the publishers who forced her to re-write The Man Who Loved Children and set it in America. Thankfully, Stead did not bow to the same kind of persuasion when it came to For Love Alone.

I’ve said I’m not going to describe my meeting with the author in this post, but I will finish it by mentioning one thing. It has always intrigued me how, in The Man Who Loved Children, Louisa helps her step mother to kill herself, or at least does not prevent it happening. When I met Stead at Monash, and asked her about this harrowing and memorable scene, she replied, ‘I could be violent with them (meaning her characters) because I was violent with myself.’

Here is a link to another contributor, who has reviewed Christina Stead: A Life of Letters by Chris Williams.

https://theaustralianlegend.wordpress.com/2016/11/04/christina-stead/

As time goes on I’ll be adding more.

On October 7, eight female crime and mystery writers will converge on Cobargo, just inland from Bermagui on the NSW coast, to take part in their inaugural crime convention.

http://fourwinds.com.au/whats-on/sisters-in-crime/

The writers are an eclectic mix, from a gynaecologist living in far north Queensland, Caroline de Costa, to a former member of the RAAF, who also has a BA in medieval history, Ilsa Evans, to a writer of historical crime (Sydney/1930s), Sulari Gentill, to yours truly, author of a Canberra-based quartet, now embarked on a sea-change mystery series.

One of the festival organisers, in a welcoming email, said that they were washing the streets of Cobargo in honour of our arrival. Thank you, Louise!

While this is an attractive idea, I wonder if it really fits a collection of crime writers, who might be more comfortable with dirty streets, even blood-stained ones?

Jennifer Rowe once referred to crime writers as ‘good housekeepers’, by which she meant that we like to tidy things up, which has an element of truth in it, at least for some exponents of the genre. But even PD James said that order is never really re-established at the end of her novels.

My approach to clean streets is that I like to dig beneath them – hardly surprising since I lived in Canberra for 30 years and turned to mysteries as a way of writing about that city.

Now what exercises my imagination is what might lie beneath the surface of an idyllic coastal town….

Authors sometimes grumble about their editors, and the question I’ve chosen as a title for this post is one I’ve often heard authors repeat.

But I’m pleased to say that I have a wonderful editor for my new novel, titled The Swan Island Connection. This novel is a sequel to the first of my sea-change mysteries, Through a Camel’s Eye, which was published in April by For Pity Sake Publishing.

The editor’s name is David Burton. David, an editor with For Pity Sake, is also an award-winning playwright and theatre director, whose plays include April’s Fool, Orbit and The Landmine Is Me. He has written a memoir titled How to be Happy. As an editor, Dave possesses that rare quality, (rare in my experience), in that he takes the trouble to see into an author’s mind, think about where he or she is trying to get to, and how he might help them to arrive.

Dave read what I am now calling the Dog’s Breakfast Draft (DBD) of The Swan Island Connection and wrote a nineteen page report. When I first saw the report, I felt daunted. There must be an awful lot wrong with the manuscript, I thought, to require this many pages. But the report, while critical, is constructively so, and that makes all the difference. In tone it is far from negative, and is full of helpful ideas and suggestions. And the very fact that someone who know what he’s talking about has paid such close attention to my DBD has given it, and me, a whole new lease of life. Thank you, Dave!

The Swan Island Connection will be my eleventh novel to be published. The first was in 1984, and since then I’ve run the gamut from good editors to woeful. Amongst the good I number Jenny Lee and Lois Murphy, and amongst the woeful, who shall be nameless, the lesbian separatist who read my book about the British atomic bomb tests at Maralinga. This was not, on the face of it her subject, and she made no effort to meet me half, or even a quarter of the way. Another was the editor who used to ring me at 6 PM, just before she left the office, to discuss editorial points that required thought and concentration. At the time this editor was assigned to me, I had a four-year-old and a baby who wouldn’t sleep, plus a deadline for the manuscript. One horrible evening I shouted at her down the phone, ‘Don’t you realise it’s jungle hour!’ I’ve felt ashamed of that outburst ever since.

Then there was my New York editor whose publishing company had bought the first two of my Sandra Mahoney Quartet (mystery novels set in Canberra, where I lived for thirty years). This editor, though I respected him, and of course felt grateful that my books were going to be published in the United States, insisted that I change all my galahs to parrots, all my jumpers to sweaters, and that I massage the text in various other unsavoury ways in order to make it more attractive to an American readership.

Recalling all that, I’ll say again – thank you, Dave!

And thanks to Bill Whitehead the cartoonist for reminding me how much I like Dickens.

My review of Suzanne Leal’s The Teacher’s Secret was published in the Fairfax newspapers this weekend. The review heading calls it ‘a novel of good and evil in a school’ and it is that. Suzanne Leal is very clear where she stands on the issue of political correctness taken to extremes.

Leal’s was a hard novel to review because I found myself more than usually tempted to give away important aspects of the plot. The fact that the ‘teacher’s secret’ is revealed quite late in the story somehow made this temptation stronger. I wonder how other reviewers feel about the problem of having to avoid plot spoilers? Does it make them nervous, the way it does me? Have they been berated by an author for making a blunder, or even giving too much of a hint? It would be interesting to compare notes.

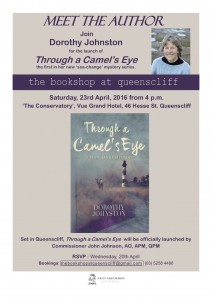

Through a Camel’s Eye, the first of my sea-change mystery series.

The ebook is also available on Amazon and other sites.

Thanks to all my friends who attended the launch in Queenscliff. It was an occasion to remember!

Joan Kerr, of Gert Loveday fame, has written a generous review of Through a Camel’s Eye which you can read here.

Thanks again to all the wonderful people who’ve helped me get this far. Through a Camel’s Eye is my tenth novel to be published. I’ve at last reached double figures -yeah! It really does feel like a milestone.

Last Friday (May 6) I gave an author talk at The Book Bird in West Geelong. Thanks to Anna, the bookshop proprietor, for hosting the event, and to everyone who came along!

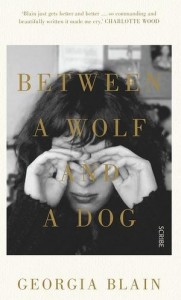

My reviews of Georgia Blain’s Between a Wolf and a Dog, and her young adult novel, Special, were published in the Fairfax newspapers this weekend. (In Australia, it’s a long weekend for Anzac Day.)

Readers of this blog will know that I don’t copy my reviews into my posts. You can read the reviews of Blain’s two books here.

Instead, I add a few thoughts that I didn’t have the space for, or go off on a small tangent of my own.

While Georgia Blain was writing Between a Wolf and a Dog, in which one of the main characters, a woman in her seventies, has brain cancer, she discovered that she herself had a malignant brain tumour. She was mowing the lawn one day when she collapsed and was taken to hospital.

There’s a very good interview with Charlotte Woods in the Fairfax papers, detailing what Blain went through, and she also wrote a series of articles about it in The Saturday Paper.

You can imagine what you’d feel like if that happened to you. You’d scarcely be able to believe that irony, or fate, could be so cruel.

Blain went back to editing the novel, which isn’t autobiographical, and produced a very fine piece of work indeed.

It’s a co-incidence that, the same weekend my reviews were published, I started reading the manuscript for The Dalai Lama in My Letterbox, sub-titled One woman’s Big Breast Adventure, by Jennifer McDonald. The books are very different – McDonald’s is based around the blog she started when she was first diagnosed with breast cancer. It’s warm and witty, at time very funny, intimate and courageous.

Blain’s is fiction, and there are other important characters besides the cancer sufferer. The two books have one thing in common, though; neither is the least bit sentimental.

Jennifer McDonald, I’m proud to say, is the Principal at ‘For Pity Sake’, publishers of my latest novel, Through a Camel’s Eye.

One last comment on Between a Wolf and a Dog. The title comes from a French expression: ‘l’heure entre chien et loup’. This means ‘the hour between a dog and a wolf’, and refers to dusk, or twilight, when an animal, possibly threatening, observed at a distance, is no longer a dog, but not yet a wolf. It’s that unsettling time which, in English, we sometimes call ‘the witching hour’. Blain has inverted the French saying to make it refer, not to dusk, but dawn, the time when the novel begins, with one of the characters who has passed a sleepless night.

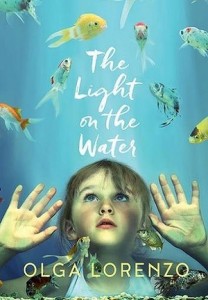

My review of Olga Lorenzo’s The Light on the Water was published in the Fairfax newspapers this weekend. As usual, when posting about a newspaper review, I’m not going to repeat the points I make about the novel, but, this time, add some information about the author’s life.

Olga Lorenzo was born in Cuba a month after the revolution that brought Fidel Castro to power. Her family left Havana for Miami when she was not quite three years old on one of the ‘Freedom Flights’.

‘It was terrible,’ Lorenzo says. ‘There were no refugee programs in place in Miami. We moved to what was called Little Havana, and everyone was speaking Spanish around me, so it wasn’t a cultural transition. The shock was that I had no toys, we had no clothes, there was no food, we had no furniture.’

When she was 22, Lorenzo moved to Australia and finished her undergraduate degree at Melbourne University, where she later went on to do a Masters and a PhD in creative writing. She currently teaches creative writing and has also worked as a journalist and sub-editor for the Melbourne Age.

Her first novel, The Rooms in My Mother’s House, published in 1996, though clearly fiction, draws largely on her family’s experiences. Twenty years on, The Light on the Water tackles very different subject matter, but with Lorenzo’s hallmark compassion and skill.

Thanks to Sydney Morning Herald literary editor, Susan Wyndham, for mentioning my forthcoming novel, Through a Camel’s Eye, at the end of my review.

‘Dorothy Johnston’s novel Through a Camel’s Eye will be published in April by For Pity Sake.’

Through a Camel’s Eye will be launched on April 23rd at the Vue Grand Hotel in Queensciff. Hope to see you there!

Last Friday, while walking 3 dogs, I tripped, fell heavily and broke my left wrist. Now I’m facing 6 weeks without being able to swim, drive or play the piano.

It’s amazing the number of dog-walking mishap/ falling down/ breaking limb/ stories I heard during my 24 hours in hospital.

One of my nurses broke her ankle after slipping on some perfectly ordinary leaves. My anaesthetist told me how he was riding his bike with his dog running obediently alongside when all of a sudden the dog dashed in front of him. He went straight over the handle-bars, but fortunately wasn’t hurt. The culprit? A pedestrian walking towards them carrying a packet of sausages. This story was made all the more vivid because the anaesthetist was sticking needles into me at the same time as he was telling it.

I’ve just tried playing a few bars of a favourite piece on the piano with my right hand only. I can see I’m going to have to do a lot of experimenting/improvising over the next few weeks.

Soon after I started blogging, I wrote a post about the importance of music to my father when he was suffering from Alzheimer’s disease, and about playing the piano at different writers’ residencies around the world.

Thinking about this, I was reminded of the poet Tomas Tranströmer and how he taught himself to play the piano left-handed after suffering a stroke.

‘Tranströmer began playing piano as a child and it became for him in his life a passion matched only by his career as a poet. Musical references and composers often appear in his poems. In 1990, he suffered a stroke that paralyzed the right side of his body and affected his speech.

This description, from the poet’s official website, and the photo of Tranströmer sitting at his piano, focused and dedicated, his right hand tucked up and his left hand making music, moved me very much. Music is as important to me as writing, and my inconvenience is nothing compared to what Tranströmer faced. Now, when I sit at the piano trying to pick out melodies with one hand, I’ll be thinking of him.

This poem is copied from Tranströmer’s official website. I don’t know if he wrote it before or after his stroke.

Allegro

After a black day, I play Haydn,

and feel a little warmth in my hands.

The keys are ready. Kind hammers fall.

The sound is spirited, green, and full of silence.

The sound says that freedom exists

and someone pays no tax to Caesar.

I shove my hands in my haydnpockets

and act like a man who is calm about it all.

I raise my haydnflag. The signal is:

“We do not surrender. But want peace.”

The music is a house of glass standing on a slope;

rocks are flying, rocks are rolling.

The rocks roll straight through the house

but every pane of glass is still whole.