My review of Julienne van Loon’s novella Harmless was published in the Sydney Morning Herald, the Age and the Canberra Times last weekend, prompting me to think again about the novella as an art form and all that’s been said about it over the last few years. As many readers and commentators have observed, the novella has been enjoying something of a come back, due in part to the digital revolution and in part, in Australia at least, to the Griffith Review novella competition, which received more than 200 entries. Julienne van Loon was a judge of this competition, along with Craig Munro and Estelle Tang.

Harmless exhibits one of the classic features of the novella, in that the action is compressed and tightly constructed – a point I make in my review. But what I didn’t go into – 600 words imposes its own kind of compression – was how that action and those characters are made richer for the reader by the scope van Loon allows herself to explore the characters’ past lives and what has led them to their present impasse.

Harmless could have been an excellent short story, tense and full of a sense of impending doom – not that those qualities are missing from the novella – but it takes longer to reach the climax. It takes its own good time.

While I was writing my own attempt at a novella, called Ashes from the Headland – it made the finals in the Griffth Review comp and you can read more about it here – I was helped in my thinking by an excellent essay called The Novella: Some Tentative Suggestions by Professor Charles May. May talks about various hallmarks of the novella, including ‘an ordered situation broken up by disorder’, a character having ‘to make a choice of nightmares’ and a setting that is ‘cut off from the everyday world of normal reality.’ All of these apply to my novella and to Harmless, a title that contains frightening levels of irony.

It’s a fascinating question, and of course one that will never be answered definitively – how long a work of fiction needs to be in order for the themes and characters to find full and satisfying expression.

My Canberra crime quartet is about to go digital – all four books at once! I’ll be offering special deals and giveaways and using this blog to let readers know about them.

The first three, The Trojan Dog, The White Tower, and Eden, are published by Wakefield Press in Australia, and the first two in America by St Martins Press. I’m glad they’re being released as ebooks this year, when Canberra turns a hundred.

I lived in Canberra for thirty years before returning in 2008 to Victoria’s Bellarine Peninsula, where I grew up. Writing a mystery series was one of the things I turned to, to try and understand Australia’s national capital both as the city I loved and as a seat of government that is often misunderstood and derided by the rest of the country. I decided early on to write four novels, one for each season, beginning with Canberra in the grip of a hard winter and ending with The Fourth Season, which is set in autumn.

I’ve always been fascinated by the physical aspects of the city, the way the clear inland light seems to promise truth, the way it shines on the Parliament’s enormous, overbearing flagmast. Canberrans have in their mist an imposing castle on a hill; they must struggle to define themselves against it, even if they do this subterraneously. The fact that inland Australian light shines brightly on our castle, that it is seldom veiled in mist like Kafka’s, makes it more, not less mysterious.

All four books feature Sandra Mahoney, and I’ll pause to say a word about her name, which has a good literary pedigree, as in The Fortunes of Richard Mahony; and an architectural pedigree as well, as in Marion Mahony Griffin, whose superb drawings were submitted along with her husband’s prize-winning design entry and are held in the National Archives. I’ve added an ‘e’ to my protagonist’s name, but that is neither here nor there; I often think about literary and architectural traditions when I’m writing about Canberra, and in some ways see my Sandra as an heir to them.

Sandra is an everywoman, falling into her first investigation, and soldiering on from there. My other series characters are a Russian IT person, Ivan Semyonov, and a Detective Sergeant called Brook, who suffers from leukaemia. Sandra’s two children, Peter and Katya, also play important roles.

And my other character is cyberspace. Electronic crime features in each book of my series. In the 1990s, when I began writing it, hardly any Australian writers were focussing on electronic crime; it seems odd to look back on that now. The ACT government once planned to make Canberra the IT capital of Australia; that’s a quaint notion now as well. Yet electronic crime seemed to fit well with the place that for thirty years was my hometown – the left hand not knowing what the right hand was doing, or pretending not to know – the government as the country’s biggest spender and therefore an attractive target for thieves and charlatans of all kinds – and something else, less easy to define.

I used to think a lot about Umberto Eco’s description of three types of labyrinth when working out the kind of mystery novels I wanted to write.

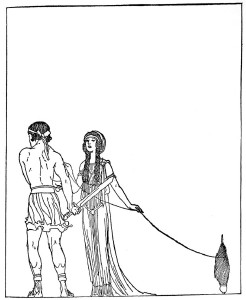

First, Eco says, there is the classic labyrinth of Theseus. Theseus enters the labyrinth, arrives at its centre, thanks to Ariadne’s thread, slays the minotaur, then leaves. He does not get lost. Terror is born of the fact that you know there is a minotaur, but you do not know what the minotaur will do.

Then there is the mannerist maze. As Ariadne’s thread is unravelled and followed, the Theseus figure discovers, not a centre, but a kind of tree with many dead ends, many branches leading nowhere. There is an exit, but finding it is a complicated task.

Finally there is the net, which is so constructed that every path can be connected to every other one. The labyrinth has no centre and no one entry or exit. Cyberspace is clearly this third kind of labyrinth. The computer criminal, hacker, virus king etc can be tracked, but the mode of tracking, of following the thread, soon corresponds to becoming lost in the maze, which indeed itself can become the minotaur.

I find this space enormously appealing, though its complexity has far outstripped by ability to comprehend it. Yet what also appeals to me is the traditional structure of a crime investigation – a fictional crime investigation, that is – the progression from a beginning to an end where the criminal is identified and caught. I like the tension that’s created by putting one inside the other, and I strove to create this tension in each of the books comprising my quartet. They represent a sizeable chunk of my writing life and I’m glad they’re going to have new lives of their own.