Much as I dislike agreeing with Ernest Hemingway about anything, I find I am in agreement with him about Chekhov’s gun.

Hemingway’s views on hunting and bullfighting would alone be enough to put me off, but when I was staying at the Chateau de Lavigny (a Swiss writers residence) back in 2006, I found a marvellous collection of letters in the library. Famous writers from Europe and the United States had stayed at Lavigny over the years and the extract below is from a letter Hemingway wrote in the 1930s to his German publisher.

Hemingway was nursing a broken arm, having shot ‘a big horn mountain sheep ram, two bears and a bull elk’. Clearly the confinement caused by his injury didn’t suit him, since his letters at that time are full of complaints.

‘I have been here for a month with my right arm broken off clean below the shoulder, so I have not answered your cables or letters. Will you please send me press reviews of Farewell to Arms and some copies of Manner. I have never yet received even one copy of Manner. If you do not treat me better about books and make me more money, I will have to get another publisher.’

Some readers might applaud this forceful attitude, but to me it smacks of the egotism I associate with Hemingway.

So what is it about ‘Chekhov’s gun’ that finds me reluctantly siding with him?

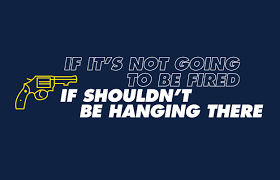

The principle, stated simply, is that writers should not make narrative promises to readers that they don’t fulfil. The image Chekhov famously used was a rifle hanging on the wall.

‘If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there.’ (quoted in Chekhov: The Silent Voice of Freedom.)

Not making false promises to readers sounds like a laudable principle, but, to return to the image of the gun, what if there’s not one hanging on the wall, but several? What if the wall is liberally decorated with guns? Should they all go off?

I’m thinking of ‘red herrings’, and the important part they play in crime fiction. Do readers feel cheated when the ‘red herring’ gun fails to go off? I don’t. I don’t mind narrative cul de sacs, or inconsequential characters making cameo appearances.

Some writers do have all the guns going off; their narratives are full of bangs and blows. I’m not that kind: I find constant violent action irritating. As a reader, I prefer to puzzle out things alongside the protagonist (or protagonists). I like room for reflection.

Hemingway mocked Chekhov’s principle and valued inconsequential details. He cited instances in his short stories of characters who appear then disappear without making an obvious contribution to the plot.

I find it a sweet irony that Hemingway managed to break his arm while killing animals for so-called ‘sport’. If the shooting accident had been in one of his stories, rather than something that had actually happened to him, where was the narrative moment for which the accident was a ‘kept promise’ of the kind Chekhov had in mind?

It would be lovely if Chekhov were able to have the last word on this, but unfortunately he can’t.

Hemingway had the last word when he committed suicide by shooting himself at the age of sixty-one. In that sense at least, all the former gunplay, the posturing and complaints weren’t false promises. The gun on the wall did go off many times and the last time it killed him.

photo of Dorothy Sayers

“Time and trouble will tame an advanced young woman, but an advanced old woman is uncontrollable by any earthly force.”

This wonderful quotation is from Clouds of Witness, a 1926 mystery novel by Dorothy L. Sayers, the second in her series featuring Lord Peter Wimsey.

I haven’t read Clouds of Witness, so I don’t know who says it, or whereabouts in the novel it comes. I should read it, being myself a lover and writer of mysteries.

I have, however, quoted Sayers’s lines quite often during the last few years. I sent them to a friend after I joined Grandmothers for Refugees. (I’m not grandmother, so I had to become an associate member.)

But I’m old enough to be a grandmother, which is the point.

I have nothing against young women. Many whom I meet are brave and wonderful, but I admit to indulging a private smile at the picture of them tumbling, gracefully, regretfully, at hurdles, while we grannies and would-be grannies, with our grey hair and whiskered chins march on.

I’m particularly mindful of the need to keep marching on as the launch of my twelfth novel approaches. I should feel proud to have got this far, and I do. I should feel grateful to all the people who have helped and continue to help me, and I definitely do. I look back at the hurdles where I fell and lay there panting, then got up again and stumbled on.

Sayers says we advanced old women are unstoppable by earthly forces. Of course it’s conceited to claim we are advanced. But I think we’re entitled to the claim when we look back at the hurdles and realise that any one of them might have been the end.

When I think of earthly forces, I mainly think of human ones, that did not want me to succeed. I don’t think of the wind and rain, the wild storms that have never been my enemies.

Thank you Dorothy Sayers, for your foresight and your strength of purpose. Thank you all the other writers of my age, who have never given up.