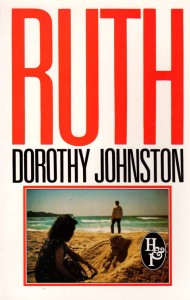

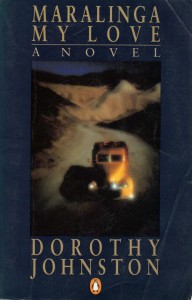

My Canberra crime quartet is about to go digital – all four books at once! I’ll be offering special deals and giveaways and using this blog to let readers know about them.

The first three, The Trojan Dog, The White Tower, and Eden, are published by Wakefield Press in Australia, and the first two in America by St Martins Press. I’m glad they’re being released as ebooks this year, when Canberra turns a hundred.

I lived in Canberra for thirty years before returning in 2008 to Victoria’s Bellarine Peninsula, where I grew up. Writing a mystery series was one of the things I turned to, to try and understand Australia’s national capital both as the city I loved and as a seat of government that is often misunderstood and derided by the rest of the country. I decided early on to write four novels, one for each season, beginning with Canberra in the grip of a hard winter and ending with The Fourth Season, which is set in autumn.

I’ve always been fascinated by the physical aspects of the city, the way the clear inland light seems to promise truth, the way it shines on the Parliament’s enormous, overbearing flagmast. Canberrans have in their mist an imposing castle on a hill; they must struggle to define themselves against it, even if they do this subterraneously. The fact that inland Australian light shines brightly on our castle, that it is seldom veiled in mist like Kafka’s, makes it more, not less mysterious.

All four books feature Sandra Mahoney, and I’ll pause to say a word about her name, which has a good literary pedigree, as in The Fortunes of Richard Mahony; and an architectural pedigree as well, as in Marion Mahony Griffin, whose superb drawings were submitted along with her husband’s prize-winning design entry and are held in the National Archives. I’ve added an ‘e’ to my protagonist’s name, but that is neither here nor there; I often think about literary and architectural traditions when I’m writing about Canberra, and in some ways see my Sandra as an heir to them.

Sandra is an everywoman, falling into her first investigation, and soldiering on from there. My other series characters are a Russian IT person, Ivan Semyonov, and a Detective Sergeant called Brook, who suffers from leukaemia. Sandra’s two children, Peter and Katya, also play important roles.

And my other character is cyberspace. Electronic crime features in each book of my series. In the 1990s, when I began writing it, hardly any Australian writers were focussing on electronic crime; it seems odd to look back on that now. The ACT government once planned to make Canberra the IT capital of Australia; that’s a quaint notion now as well. Yet electronic crime seemed to fit well with the place that for thirty years was my hometown – the left hand not knowing what the right hand was doing, or pretending not to know – the government as the country’s biggest spender and therefore an attractive target for thieves and charlatans of all kinds – and something else, less easy to define.

I used to think a lot about Umberto Eco’s description of three types of labyrinth when working out the kind of mystery novels I wanted to write.

First, Eco says, there is the classic labyrinth of Theseus. Theseus enters the labyrinth, arrives at its centre, thanks to Ariadne’s thread, slays the minotaur, then leaves. He does not get lost. Terror is born of the fact that you know there is a minotaur, but you do not know what the minotaur will do.

Then there is the mannerist maze. As Ariadne’s thread is unravelled and followed, the Theseus figure discovers, not a centre, but a kind of tree with many dead ends, many branches leading nowhere. There is an exit, but finding it is a complicated task.

Finally there is the net, which is so constructed that every path can be connected to every other one. The labyrinth has no centre and no one entry or exit. Cyberspace is clearly this third kind of labyrinth. The computer criminal, hacker, virus king etc can be tracked, but the mode of tracking, of following the thread, soon corresponds to becoming lost in the maze, which indeed itself can become the minotaur.

I find this space enormously appealing, though its complexity has far outstripped by ability to comprehend it. Yet what also appeals to me is the traditional structure of a crime investigation – a fictional crime investigation, that is – the progression from a beginning to an end where the criminal is identified and caught. I like the tension that’s created by putting one inside the other, and I strove to create this tension in each of the books comprising my quartet. They represent a sizeable chunk of my writing life and I’m glad they’re going to have new lives of their own.

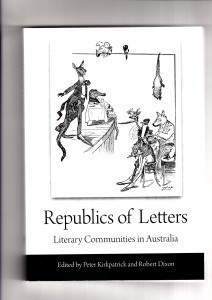

This post is a follow-on from my last one, in that I’m writing it out of a resurgence of memories regarding literary Canberra. A nice bit of serendipity over the weekend has resulted in my website going live at the same time as James Ley’s review of ‘Republics of Letters: Literary Communities in Australia’, edited by Peter Kirkpatrick and Robert Dixon, was published in The Australian. It’s a thoughtful review, engaging with the book’s arguments about literary communities and the fraught nature of the term, and including a wide range of examples.

And it’s taken me back to D’Arcy Randall’s chapter on 7 Writers.

D’Arcy begins by remarking how, in ‘the 1970s, Australia’s thriving literary scene was typically associated with networks of male writers in such urban bohemian venues as Balmain in Sydney and Carlton in Melbourne.’

And how well I remember that! I was trying to be a writer in Carlton in the ‘70s and it was very important to drink in the right pubs, and to look the part. When my journalist partner was offered a job in the Press Gallery, instead of moving to Canberra with him, I decided on a foolish geographical compromise called Sydney. Then, after ten months on the highway – I was often too poor to afford the train fare and I’m lucky I didn’t end up buried in the Belanglo State forest – I gave in and settled in Canberra.

The relief was enormous. Here was a small, feisty literary community – and yes, I use the term ‘community’ aware that contains many kinds of ambivalence – where it didn’t matter what pub you drank in, or if you drank in any pub at all.

D’Arcy has been painstaking in gathering information about our writers’ group – where we met, how often, what we did, how many books we published between us. How torn we often were!

Of course, we’re still publishing, but 7 Writers ended its collective life in the late 1990s, and with, its end, the centrifugal pull, the push outwards, the ongoing battle between solitary creative compulsion and the possibility of actually sharing flowed away.

I’ve always liked Edith Wharton’s description of how writers view their work, indeed are forced to view their work, from the back of the tapestry. They can’t walk around the front and look at it; this is an impossibility. Well, writers’ groups are like that too, I’m discovering. It’s a strange, unsettling, delightful experience to have something you participated in, were intimate with, for almost twenty years, presented from the right side of the tapestry, but without the presentation glossing over or hiding the knots. Thank you, D’Arcy!

And ‘Republics of Letters’ contains other treats as well, including a chapter on my favourite Australian writer, Christina Stead and her no-longer neglected masterpiece, The Man Who Loved Children.

* D’Arcy Randall was born and educated in the US, but during the 1980s she lived in Brisbane, where she was senior editor at the University of Queensland Press. She there worked with Marian Eldridge and Marion Halligan on their first books. After returning to the US, she founded the journal Borderlands: Texas Poetry Review and began a teaching career at the University of Texas at Austin.