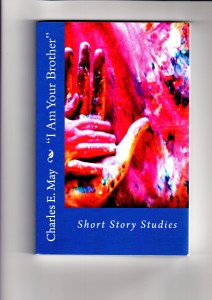

I first came across Professor Charles May’s blog eighteen months ago and was immediately struck by the quality of May’s insights into the short story form. May has published 8 books and over 300 articles on the subject of short stories, and I Am Your Brother is the culmination of forty years of teaching and thinking about this often misunderstood and disparaged prose form. True scholarship, in the sense of being heart-felt as well as erudite, is unmistakeable, and I recommend this book both to readers and writers of short stories, and to those who have not, up until now, given them much thought.

One of May’s central concerns is that short stories have suffered in the past, and continue to suffer, by being compared, in a simplistic way, to novels; by being considered no more than bits of novels, constructed according to the same formal patterns and with the same narrative ends in view. He sets out to dismantle these false assumptions and he does so very convincingly.

Short stories have ancient ancestors, and have remained connected to their roots in the sacred parable, allegory and myth. The everday passage of time, cause and effect, the development of individual characters within a social framework are all hallmarks of the novel from the eighteenth century onwards. In the short story, because of its shortness, and because its writers started out with very different aims, time is just as likely to be compressed, or frozen.

In discussing Edgar Allan Poe’s approach to the short story, May points out that it ‘reflects the basic paradox inherent in all narrative: the writer’s restriction to the dimension of time juxtaposed against his or her desire to create a structure that reflects an atemporal theme. Because of the shortness of the short story, the form gives up the sense of real time, but compensates for this loss by focusing on significance, pattern and meaning.’

Important themes for me, in I Am Your Brother, are the sense of mystery to be found in the best short stories, how they give an outer shape to inner meanings, manage to convey what can’t be put directly into words and eschew so-called rational explanations. May quotes Flannery O’Connor who ‘once said that what the short story writer sees on the “surface will be of interest” only as it can be gone through “into an experience of mystery itself.”

From Boccaccio’s The Decameron up to the present day, May illustrates his points with pertinent and interesting examples. My knowledge of short stories and what makes them essentially different from long prose forms, has been greatly enhanced by reading this book.

Above is the text of my Amazon review of I Am Your Brother, but I thought I would add a few more personal thoughts about it on my blog.

Having had eight novels published, and with a ninth (The Fourth Season) soon to be released, I am better known as a novelist than a short story writer. However, a few of my short stories have had multiple publications in anthologies and have found a readership. Two of these are ‘The Boatman of Lake Burley Griffin’ (Canberra Tales, Below The Waterline, The Invisible Thread) and ‘Two Wrecks’ (Best Australian Stories 2008 and Best Australian Stories – a ten-year collection, 2011).

The success of these stories, coupled with my experiment in self-publishing an ebook collection, Eight Pieces On Prostitution, has got me thinking about the place of short stories in my writing life.

Like many fiction writers, I always know when an idea is a ‘short story idea’, and I always hear, with my inner ear, before I set a word down, the tone of voice I will need to sustain. Needless to say, this is very different from how I begin the project of writing a novel. I have often been criticised, and, I am ashamed to say, too often bowed to the criticism, that my fiction is elliptical and indirect when it should be straightforward. I have often been asked to explain or clarify character and motivation when this was the last thing that I felt like doing.

Reading I Am Your Brother made me feel that my instincts were right all along, and that those criticisms came from perspectives and expectations that were alien to me, and to which I should never have tried to reconcile myself.

Thanks for your comment Joan. I think the knitting/tapestry analogy is a good one! I have the sense that Alice Munro and other great short story writers have been badgered for years to write novels, so perhaps that remark is a reaction of some kind? Charles May quotes Munro at length in ‘I Am Your Brother’, and describes her insistence that only in writing short stories can she get the kind of tension she needs. Her attempts at novels – begun in response to criticism – went flat and flabby. I recall having a conversation with you about some of your short short stories; I may not have remembered exactly, but you were quite clear about them being the right length, and that you didn’t want to expand them.

Yes, I probably did say that. I am more equivocal these days. Perhaps my reaction was more insecurity that, having achieved something, I didn’t want to mess around with it! I used to feel the same way about poems – I had the feeling that once I had achieved a certain form it was finished. Sometimes I still think that, but quite often if I leave enough time I do change things that I thought were finished.

That said, there are certain short stories I think are quite perfect and it’s rare to say that about a novel.

Thanks again, Joan.

I have gone back to Edgar Allan Poe, and he does have some interesting things to say about the short story form, about its unified effect and the reader’s ability to hold the whole in her/his mind at once.

Hi Dorothy

I read somewhere that Alice Munro said she’d never read a novel that wouldn’t be better as a short story. Hyperbole, perhaps (War & Peace? Middlemarch? Ulysses?) but it does suggest that for her it’s a matter of mindset rather than to do with certain ideas demanding that form. It’s probably a lot to do with what she notices and the resonance ordinary events have for her. I was thinking of those widescreen novels as like a piece of loose knitting on very big needles and a short story perhaps as a very intricate square of tapestry. But that doesn’t get the dimension of depth in the short story or its spiderweb quality, almost invisible but so strong.